The eighth episode of Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey, “Sisters of the Sun,” focused on female scientists who majorly influenced astronomy and astrophysics. Here’s the rundown (uh, it’s not possible to spoil the plot of Cosmos, is it?): because at the time women couldn’t receive science degrees at Cambridge where she attended lectures, Cecilia Payne left her native England to study astronomy at Harvard. With the help of Annie Jump Cannon – who was the first to organize and classify the stars based on their temperatures – Payne discovered that stars are mostly composed of hydrogen and helium, which she then realized are the most abundant elements in the universe. Otto Struve, a Russian-American astronomer and man, said that her 1925 thesis, titled Stellar Atmospheres, A Contribution to the Observation Study of High Temperature in the Reversing Layers of Stars was “undoubtedly the most brilliant PhD thesis ever written in astronomy.” (He did die in 1963, so perhaps he missed a few of the recent ones, but still.)

Watching the episode last night, as usual, I felt a little inadequate to the genius minds that not only comprehend amazingly complex science, but also make seemingly extraneous connections to fuel new discoveries. (This feeling of inadequacy, by the way, I take as a great great motivator.) The female pioneers featured on last night’s Cosmos were, just like any of the males we generally learn about, brilliant thinkers. And they – like most women in any field even today – made these scientific strides facing harsh adversity. Women in science are rare, precisely because of the gendered setbacks (like not awarding degrees in science in the past, or still relevant today, mythologizing that women are bad at math).

At the same time, female scientists rarely get the attention they deserve. So last night’s episode perhaps attempted to redeem this sexism in historical narrative.

But then again, maybe if Cosmos focused on women in science alongside men all the time, in each episode… maybe it wouldn’t need an entire episode dedicated to female scientists. Women have made equally important contributions consistently (just take a look at this Wikipedia list of female scientists before the 21st century!) – and have been omitted from previous episodes. Such as Caroline Herschel, whose brother William was featured in episode four, “A Sky Full of Ghosts,” although both were equally as interested and active in astronomical discoveries. She discovered M110 (NGC205) – a satellite of the galaxy Andromeda – and discovered several comets.

OK, can we talk about why there are no women scientists mentioned in #Cosmos now? Let’s talk about exploration of the Milky Way black hole.

— Matthew R. Francis (@DrMRFrancis) March 31, 2014

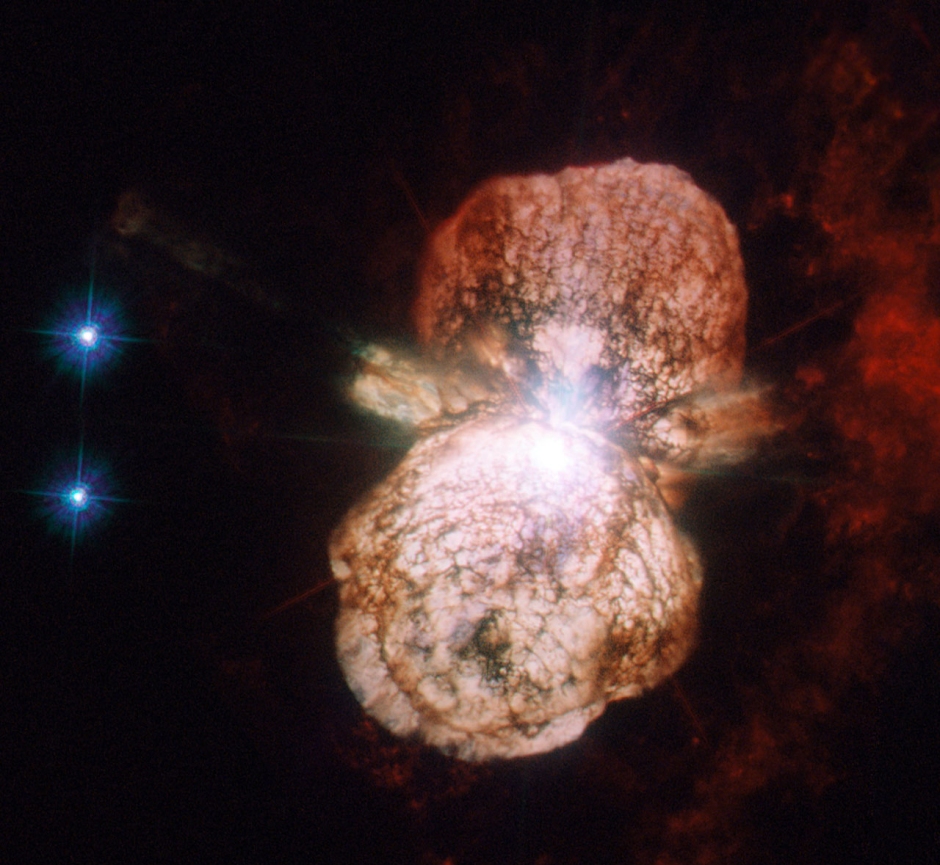

But also, last night’s episode also mentioned something that I feel like I should have heard about before? There’s a huge mega supermassive star called Eta Carinae only 7,500 light years away that’s going to explode perhaps in our lifetimes. (Note: nothing really ever happens in our lifetimes. We exist for a miniscule portion of time, and we can barely see anything from Earth, so what are the chances?!) From NASA:

Eta Carinae is not only interesting because of its past, but also because of its future. It is one of the closest stars to Earth that is likely to explode in a supernova in the relatively near future (though in astronomical timescales the “near future” could still be a million years away). When it does, expect an impressive view from Earth, far brighter still than its last outburst: SN 2006gy, the brightest supernova ever observed, came from a star of the same type, though from a galaxy over 200 million light-years away.